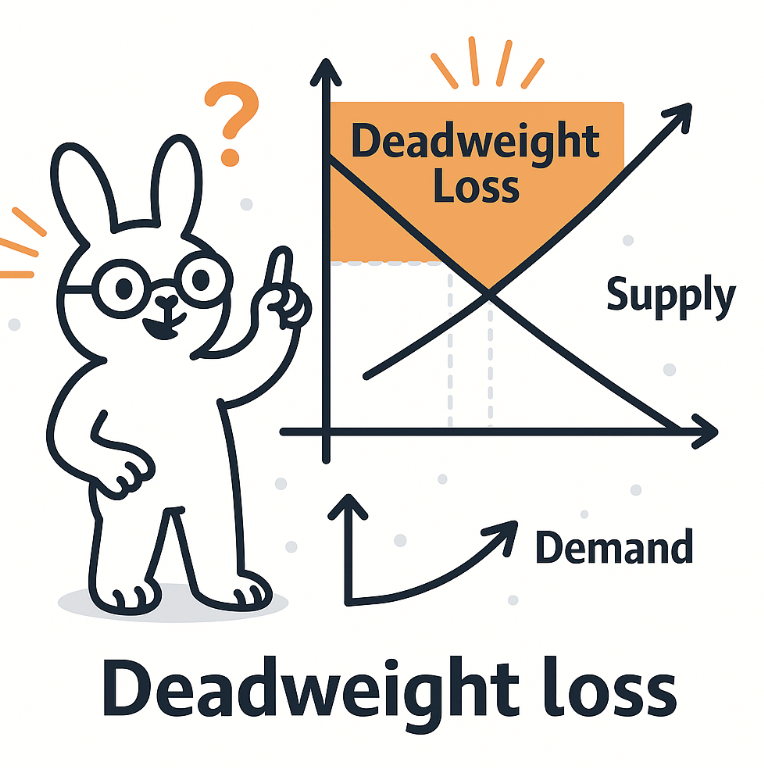

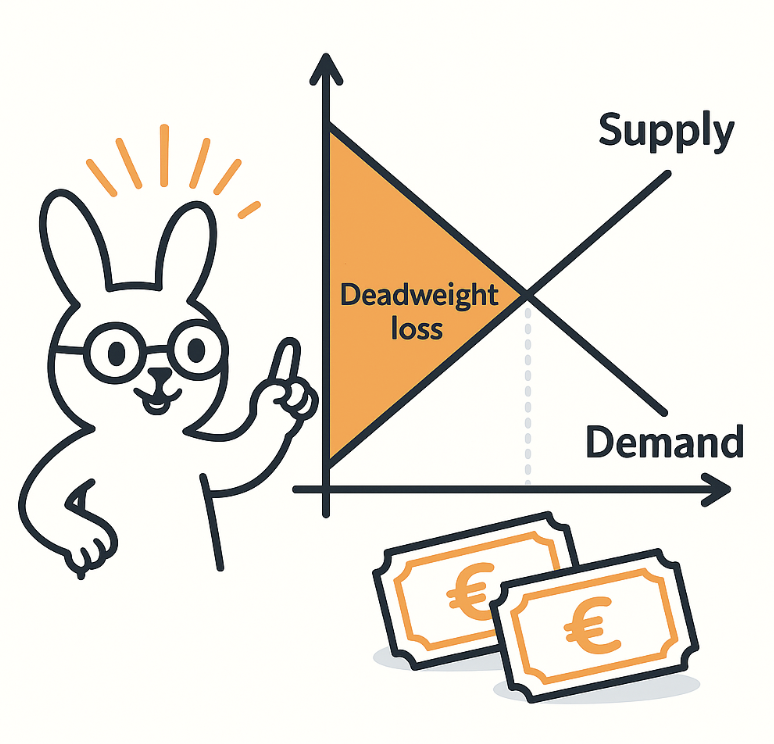

How deadweight loss works

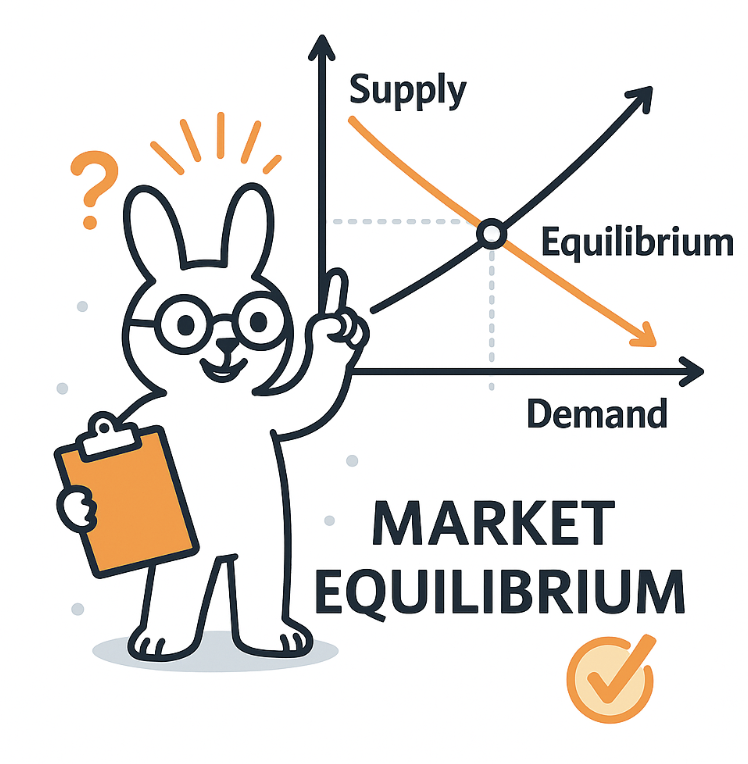

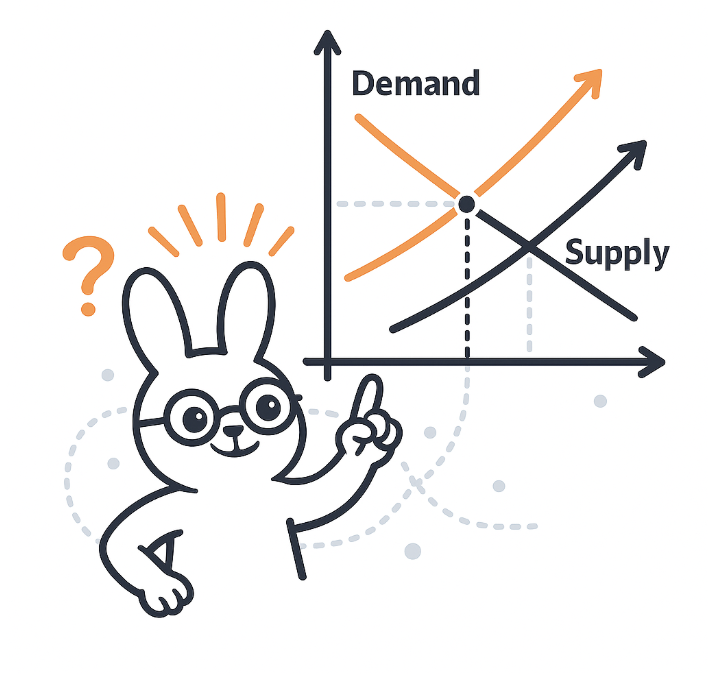

Deadweight loss happens when something prevents buyers and sellers from making trades they both would have benefited from. A tax, price ceiling, subsidy, or market restriction creates a gap between what consumers are willing to pay and what producers are willing to accept.

Because of this gap, some mutually beneficial transactions disappear - fewer people buy, fewer firms produce, and the market moves away from its efficient level. The value of those “lost” trades is the deadweight loss.